Even scientists see the beauty in autumn leaves. “I can still remember a hike when I was young," says Howard Neufeld, professor of plant ecophysiology at Appalachian State University. "The leaves were just a golden yellow, the air was clear, the sky was absolutely blue.”

“When you walk through something like that… There's nothing better.”

- Howard Neufeld

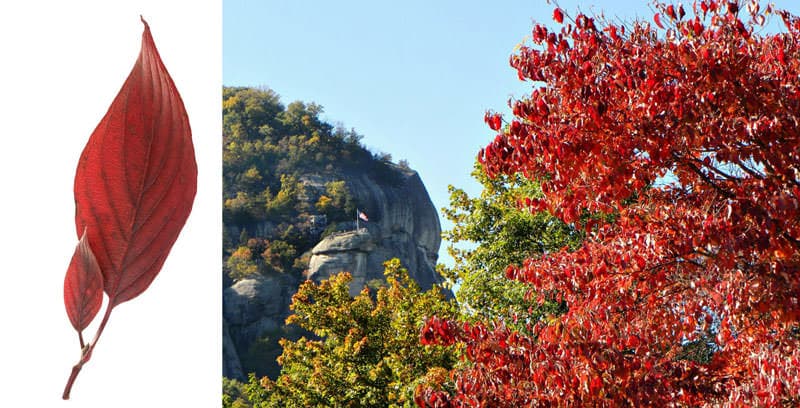

Which might do for the average person. The leaves change, the forest fills with bright yellows, vivid crimson. If you drive a mountain two-lane, scatterings of vibrant orange blow across the highway. Leaves pile around the base of split-rail fence posts, scatter against the sides of tobacco barns.

Again: enough for you and me to just see. Neufeld sees and asks: why? What do the trees get out of it? People get joy from looking, from kicking our feet through the crunching leaves on the ground, from smelling apple butter, pumpkins, smoke. Appalachian towns, adapting to that appreciation, get tens of millions of dollars offering food, drink, lodging — and history and experience. And people have also adapted to the timing of that sensory bonanza, planning festivals and harvest fairs around the peak of leaf color.

"If you had time lapse photography," Neufeld says, "you could watch the trees start to turn at the top of the mountain and then every week move down the side about a thousand feet." Mount Mitchell and other peaks tend to peak around late September, Boone peaks reliably in mid-October, Asheville a week later, and so on until you reach the Piedmont and Raleigh in November. If you could watch from space you could take climate into account and watch the color move south down the spine of the mountains, too. And though you'll see those bright yellows, reds, and oranges, Neufeld reminds you that fall has other colors too. Deciduous magnolia leaves turn a chocolate brown that makes a nice partner to the pale brown of corn sheaves and haybales. And color varies with a lot more than elevation.

For one thing, whereas New England features overwhelmingly beeches, birches, and maples, making for large blotches of single colors, western North Carolina has an enormous variety of trees — the Smokies, in fact, peppered with microclimates, host some 120 species of tree, the greatest variety in the United States. That variety gives the southern Appalachians a broader spectrum – a patchwork quilt of mountainside color.